Yesterday, while listening to one of my favorite radio shows, “Ça Rentre au Poste” on Montreal’s 94,3FM, I caught the segment they call “Revelations.” A caller phoned in claiming he had been abducted by aliens.

Now, I’ll admit, I’ve heard a lot of these kinds of stories before. Some sounded far-fetched, others felt rehearsed. But this one was different. The caller was calm, consistent, and almost too ordinary to dismiss. There was something about the way he told it that made you wonder, what if he’s telling the truth? From what I was hearing, he definitely thought he was.

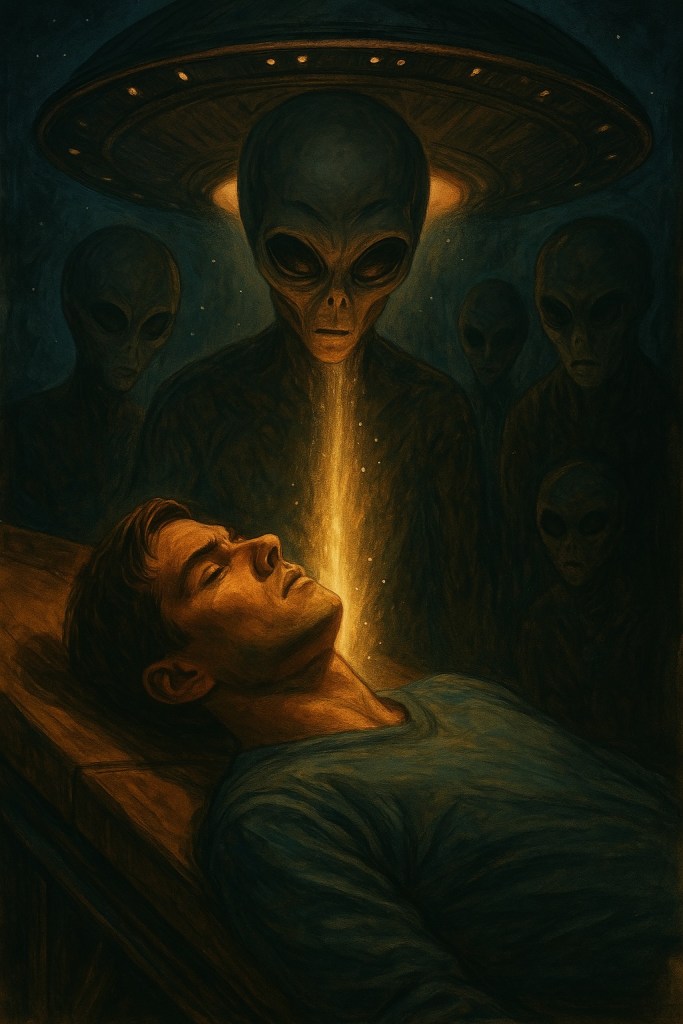

Alien abduction stories are a unique part of modern folklore. They have developed a legacy and often follow a similar pattern. You often hear about a strange light in the sky. Lost time, hours and sometimes days that can’t be explained. Fragments of memory involving bright rooms, tall beings, or medical examinations. And the lingering aftereffects, anxiety, vivid dreams, sometimes even physical marks.

Whether you believe these stories or not, they’ve become a cultural phenomenon. From the Betty and Barney Hill case in the 1960s to countless accounts since, abduction narratives have shaped how we think about extraterrestrial contact. They’re not just science fiction tropes, they’ve become part of our collective imagination.

These stories matter. What strikes me most is the impact these experiences have on the people who claim them. For many, it’s not about proving anything to the world. It’s about trying to process something deeply unsettling, something that changed the way they see reality. Some have even sought psychological help following their alleged experiences. And even if you doubt the literal truth of abductions, the stories themselves reflect something important, humanity’s ongoing fascination with what lies beyond.

These stories had a part in influencing how I wrote Galaxy’s Child. When I was developing Galaxy’s Child, I thought a lot about the psychology of contact. What would it really mean to come face-to-face with something not of this world? Would we be curious? Terrified? Changed forever?

For me, the abduction stories weren’t about the details of probes or spacecraft. They were about the human reaction, the way ordinary people describe extraordinary encounters, and how those encounters ripple through the rest of their lives.

That’s why, in Galaxy’s Child, first contact and hidden truths aren’t treated as spectacle. They’re treated as something deeply personal. Because in the end, alien abduction stories aren’t about aliens. They’re about us. About how we grapple with the unknown, how we handle fear, and how Philip Anders searches for meaning in the incomprehensible.

The radio caller yesterday may never convince the skeptics. But he reminded me why these stories endure. They make us look up at the night sky a little differently. They force us to ask, are we alone? And whether you believe in abductions or not, that question is powerful enough to shape both science fiction and science fact.