If there’s one idea that has captivated scientists and storytellers, including myself, it’s the wormhole concept. A tunnel through space-time, essentially a cosmic shortcut. In theory, it is a way to slip from one part of the universe to another without spending millennia crossing the void.

This week, two fascinating pieces of research remind us that wormholes are not just the stuff of imagination, they’re a real part of physics, even if still more theory than fact. Astrophysicists at RUDN University published a paper showing that traversable wormholes could, at least on paper, exist in our expanding universe using what’s called the Friedmann model which is a mathematical description of cosmic expansion. As far as I understand it, they showed that wormholes could remain stable if supported by “dustlike” matter. That’s a big deal because earlier models required exotic, negative-energy matter, something we don’t know how to produce or even if it can exist. By contrast, this approach relies on more familiar physics.

Does this mean we’ll be building wormhole highways anytime soon? Not exactly. The models are still highly theoretical. The math doesn’t give us engineering blueprints, it only suggests the idea isn’t impossible.

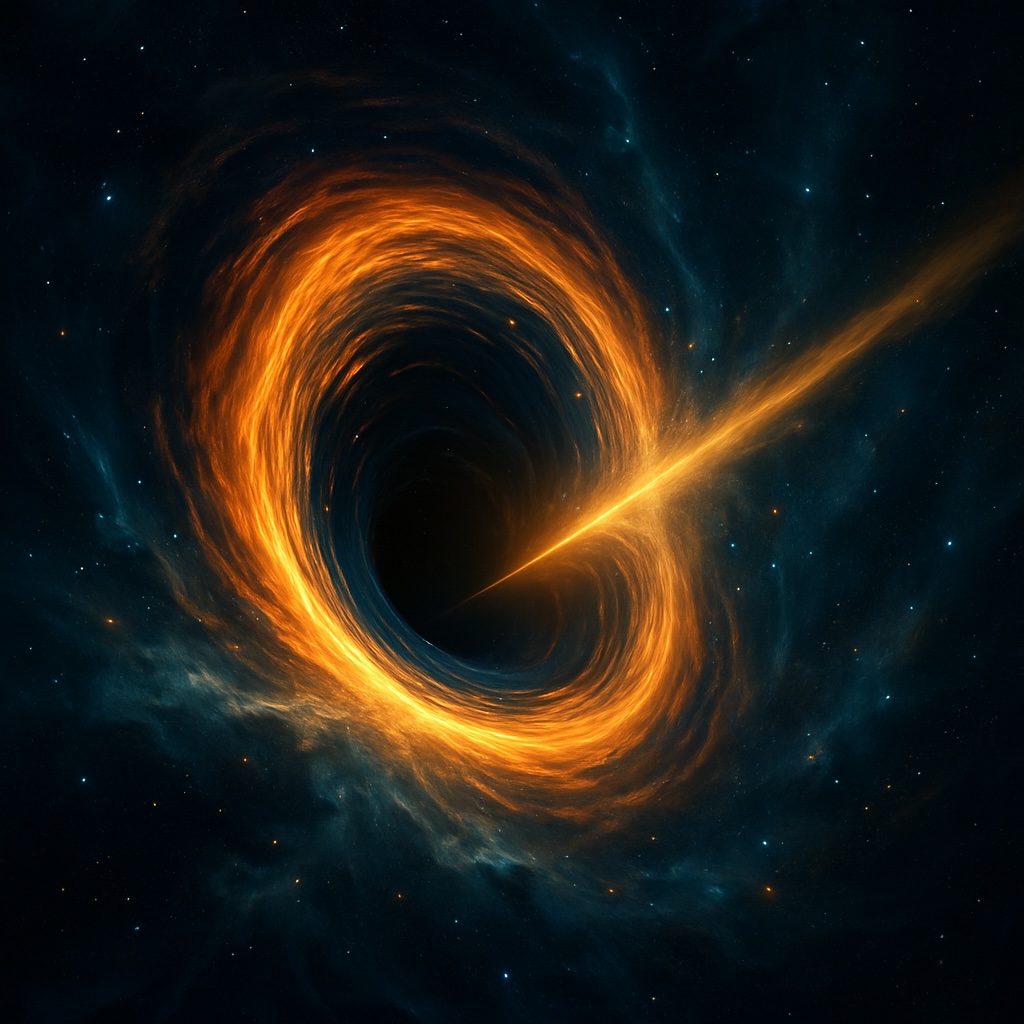

Another recent study looked at what wormholes might look like if they exist. Just as black holes bend light and cast distinctive “shadows,” wormholes would also leave visual signatures. Gravitational lensing around a wormhole’s throat could distort background light, producing strange rings, arcs, or shadows. In other words, even if we can’t travel through one, we might one day spot a wormhole by what it does to the light around it. It’s a tantalizing idea, the universe could already be threaded with tunnels, we would just need the right eyes to see them.

Science fiction, of course, has never been shy about wormholes. In Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, a stable wormhole becomes the heart of the show, a strategic and spiritual crossroads of the galaxy. Stargate gave us wormholes as portals, linking distant worlds at the push of a button. Interstellar portrayed a scientifically inspired wormhole as a shimmering sphere near Saturn, both beautiful and terrifying. And in Contact, Jodie Foster’s journey through a network of wormholes was imagined with the guidance of Carl Sagan himself, making it one of the most scientifically grounded depictions ever put to screen.

In fiction, wormholes are convenient, dramatic, and most of all, big enough for a starship to fly through. Reality, at least so far, is much less cinematic. Theoretical wormholes might be microscopic, unstable, or one-way. They might exist only in the math, never forming in the real universe. And even if they do exist, we might only ever know them by their shadows, not by walking through them.

When I created the YF-223, I didn’t want to simply copy “warp drive” or “Stargates.” Faster-than-light travel in Galaxy’s Child was inspired by science fiction’s leaps, but also grounded in the curiosity and caution of real physics. Because in the end, wormholes and FTL drives aren’t just about technology. They’re about what kind of species we become if we ever find a way to cross the ultimate boundary. Philip Anders doesn’t get to debate whether wormholes are real, he has to decide what to do when the unknown is staring him in the face.

And maybe one day, so will we.